Poetic licence in the library – bilingual poetry in 64 languages, Made in Manchester

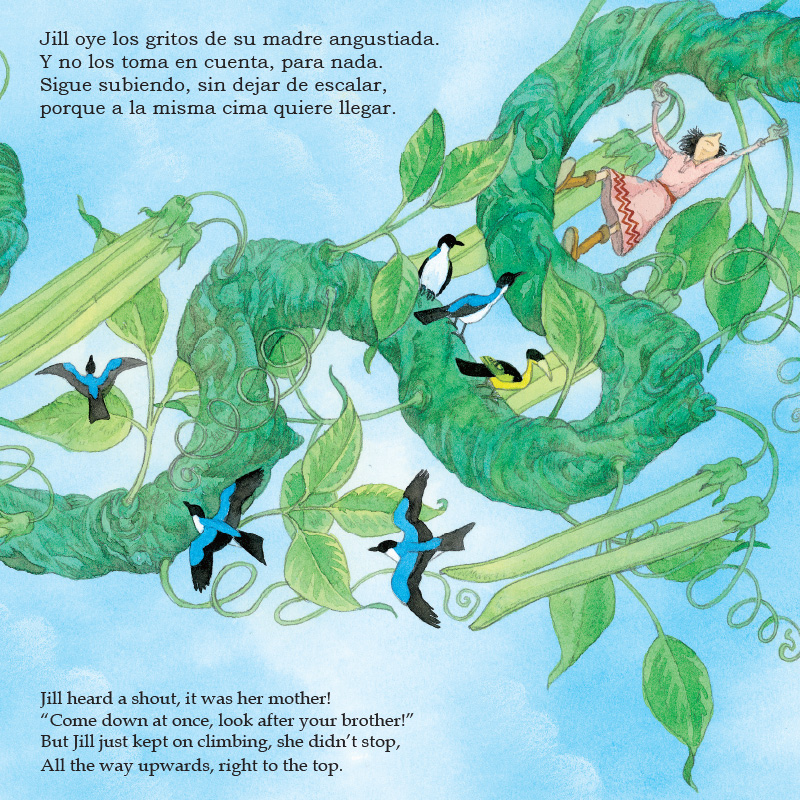

While one of the areas we specialise in is publishing bilingual books for children, we’re always on the lookout for other bilingual initiatives out there, especially when schools are involved.

So we were really taken by the fact that in Manchester, one of the most vibrant and multicultural cities in England, a poem by Zahid Hussain is now taking centre stage on screens at the Central Library. With English on one side and other languages on the other, the ultimate aim is to capture all 200 languages spoken in Manchester.

Translating from one language to another is a real art, and sometimes words are simply not translatable – with bilingual poetry books, songs and rhymes especially, since every language has its own rhythm, it can pose a real challenge. The Manchester project is especially relevant as a great example of “living language” as pupils from local schools have added lines in their own mother tongue, or heritage language. There’s a sculpture as well, so those who prefer other creative arts get a chance to contribute.

Manchester has a particularly proud literary heritage. It was the site of the first public lending library in the UK, following the 1850 Public Libraries Act: author Charles Dickens spoke at the opening ceremony and William Thackeray also attended. The city is now a UNESCO City of Literature, joining Baghdad, Barcelona, Dublin, Melbourne, Prague, and Reykjavik.

Poetry isn’t the only aspect of converting one language to another that can be problematic for translators of bilingual books and texts. Did you know that while dogs say “woof” or “bow wow” in English, for instance, they mostly say “guau” in Spanish and “waouh” in French? Had you heard that some scientists are pretty convinced that most animals also have regional accents, from whales to wolves, or that sometimes it even seems as if their communication patterns actually differ between related groups?

Animal sounds are one area that requires imagination - if you have a lot of onomatopoeia like "splish" or "splosh" or "whee" in a bilingual story or poem, it requires real skill to translate. Every language has its own quirks. Sometimes the easiest option is to leave the word as it is in the original text – though you need to be very careful sometimes that the sound of the word in one language isn’t going to unintentionally cause offence or hilarity in another...

References

(Unless otherwise stated, all links were accessed on 15 July 2019)

So we were really taken by the fact that in Manchester, one of the most vibrant and multicultural cities in England, a poem by Zahid Hussain is now taking centre stage on screens at the Central Library. With English on one side and other languages on the other, the ultimate aim is to capture all 200 languages spoken in Manchester.

Translating from one language to another is a real art, and sometimes words are simply not translatable – with bilingual poetry books, songs and rhymes especially, since every language has its own rhythm, it can pose a real challenge. The Manchester project is especially relevant as a great example of “living language” as pupils from local schools have added lines in their own mother tongue, or heritage language. There’s a sculpture as well, so those who prefer other creative arts get a chance to contribute.

Manchester has a particularly proud literary heritage. It was the site of the first public lending library in the UK, following the 1850 Public Libraries Act: author Charles Dickens spoke at the opening ceremony and William Thackeray also attended. The city is now a UNESCO City of Literature, joining Baghdad, Barcelona, Dublin, Melbourne, Prague, and Reykjavik.

Poetry isn’t the only aspect of converting one language to another that can be problematic for translators of bilingual books and texts. Did you know that while dogs say “woof” or “bow wow” in English, for instance, they mostly say “guau” in Spanish and “waouh” in French? Had you heard that some scientists are pretty convinced that most animals also have regional accents, from whales to wolves, or that sometimes it even seems as if their communication patterns actually differ between related groups?

Animal sounds are one area that requires imagination - if you have a lot of onomatopoeia like "splish" or "splosh" or "whee" in a bilingual story or poem, it requires real skill to translate. Every language has its own quirks. Sometimes the easiest option is to leave the word as it is in the original text – though you need to be very careful sometimes that the sound of the word in one language isn’t going to unintentionally cause offence or hilarity in another...

References

(Unless otherwise stated, all links were accessed on 15 July 2019)

- Animals with Accents (2016), National Geographic, 8 April 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com.au/animals/animals-with-accents.aspx

- Anniversary of first public library (2002), BBC News, 5 September 2002, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/2238494.stm

- Bilingual quick tips (c2017), Literacy Trust, https://literacytrust.org.uk/early-years/bilingual-quick-tips/

- Black, M. (2019) Manchester poem explains why the city is so great - in 64 different languages, Manchester Evening News, 12 July 2019, https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/in-your-area/manchester-poem-explains-city-great-16577563

- De la Rosa Regot, N (2015), Translating sounds: the translation of onomatopoeia between English and Spanish End-of-Degree Paper Universitat de Barcelona, http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/109643/1/TFG_Estudis_Anglesos_2015_%20DeLaRosa_Nuria.pdf

- Friedman, U. (2015), How to Snore in Korean: The mystery of onomatopoeia around the world, The Atlantic, 27 November 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/11/onomatopoeia-world-languages/415824/

- Manchester UNESCO City of Literature (c2019), Manchester Literature Festival, http://www.manchesterliteraturefestival.co.uk/pages/manchester-unesco-city-of-literature-38018

- Ward, D. (2002), First library of the people marks 150 busy years, The Guardian, 17 September 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/sep/17/books.education

- Woof Woof: Dog Barks in Different Languages (2015), Bird Gei, 24 November 2015, https://birdgei.com/2015/11/24/woof-woof-dog-barks-in-different-languages/

Related Posts

-

A Few Fun February Facts

-

Spotlight on Dari

-

EAL: The home language as a practical strength

-

When is a fruit not a fruit? When it’s a tomato…which is also a vegetable...

-

Sing something simple – using songs for language learning

-

Languages for SEN: The origins of Braille, Sign Language and Makaton

-

Amazing Audio Books - And How They Can Help Literacy Skills

-

Spotlight on Irish

-

New Year Resolutions

-

Bicycles, balls and Video Assistant Referees - is June the month of exercise?